Not only does war destroy property, kill people, and injures them, it drives them out of their minds. That’s what war is all about. That’s what I learned from painful experience …

Toshiko Saeki, Hibakusha Testimony. Accessed 8 October 2022. http://www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/virtual/VirtualMuseum_e/visit_e/testimony_e/testimo08.html

There is nothing glorious about war.

Whether you win or lose, it is nothing but emptiness, anger.

Trauma, Eva Hoffman says: “is the contemporary master term in the psychology of suffering, the chief way we understand the personal aftermath of atrocity and abuse,” and it may also be “our psychological culture’s name for extreme suffering, derived from our way of deciphering the self… the language of depth psychology … through which we have come to interpret the affective aftermath of atrocity.”

Survivors of atrocities are said to “have been traumatised,” and as such struggle with memory and forgetting and how to come to terms with the trauma and find ways to continue with their lives. These first generation survivors are scarred by their experiences, with their wounds also being passed to subsequent generations, where Hoffman tells us that their “legacy … [is] not a processed, mastered past, but the splintered signs of acute suffering, of grief and loss.” In “The Generation of Post-memory”, Marianne Hirsch describes this sense of trauma being passed down through the generations as “post-memory”, which “describes the relationship of the second generation to powerful, often traumatic, experiences that preceded their births but that were nevertheless transmitted to them so deeply as to seem to constitute memories in their own right.”

There have always been artists who respond to historical atrocities both as survivors and witnesses; in his article “Mutually Assured Decorum”, Ashley Rawlings describes the work of a number of mostly Japanese artists responding to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, events which led to the surrender of Japan and the end of the fifteen-year Pacific War. Rawlings opens with the controversial artwork called Making the Sky of Hiroshima “PIKA!” (orピカッ!) by the artist group Chim↑Pom, staged in 2008 for Hiroshima MOCA which was said by the group to be an artistic “call for peace.” (see figure 1).

The public response to the incident, particularly from the Hiroshima community, was “sharp criticism and condemnation,” where critics said the work “crossed the line of decency” because “pika” referenced “pikadon,” a mimetic word created by the hibakusha , “who had not known even the word ‘atomic bomb’ at the time, expressing what they experienced in the explosion with ‘PIKA’ as the flash and ‘DON’ as the roaring blast that followed” the sound ‘PIKA’ came to stand for the A-Bomb” , the artwork was therefore synonymous with the atomic blast.

Following the PIKA incident Takao Shimamoto, Director General of the Citizens Affairs Bureau for the City of Hiroshima, commented, “This work of art, a jarring reminder of the atomic bombing, is distressing to many citizens of Hiroshima, and particularly the A-bomb survivors. Such works must not be tolerated and must be apologized for sincerely.” This apology duly came on 22 October 2008, when the director of Hiroshima MOCA, Dr Yasuo Harada, released an apology for the controversial piece, and in a televised press conference at Hiroshima City Hall on 24 October 2008 stated: “The museum would like to apologise on behalf of a staff member who failed to stop the artists from an act that went too far while she was involved in observing it.”

At the same press conference, the leader of Chim↑Pom, Ryuta Ushiro, said:

“We would like to carefully consider how to best express our regrets to the Hiroshima community… I know what we did for our art is controversial and it upsets me if this has hurt the feelings of hibakusha. Our aim, though, was to capture the attention of young people, who haven’t experienced war.”

Rawlings asserts that the “codes of decorum… in Hiroshima, at least, are firmly entrenched” (Rawlings: 97) especially by the hibakusha, but points out that in the “relatively neutral spaces… outside of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” artists seem to be more free of such constraints, with “Post-war Japanese art and pop culture being full of references to Japan’s nuclear experience, ranging from the reverent to the absurd.”

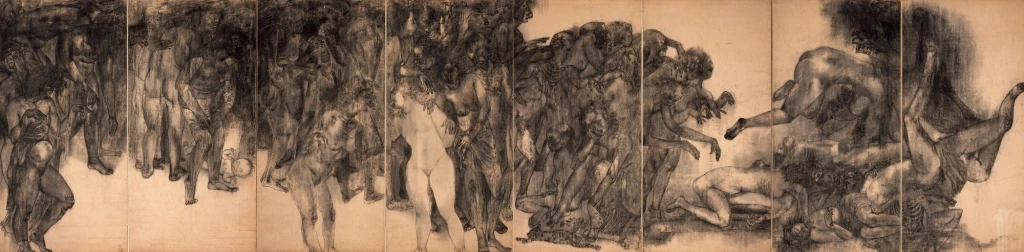

The Hiroshima Panels (Figure 2), a series of fifteen large painted panels measuring 180 centimetres high by 720 centimetres wide, by the artist couple Iri and Toshi Maruki, were the result of over thirty years of collaboration which began soon after they travelled to Hiroshima in 1945, shortly after the bombing, to assist relatives who had survived the nuclear attack. This “haunting series of expressionistic paintings” viscerally depict the aftermath of the war, where they “painted some nine hundred human figures” for the first painting alone, saying:

We thought we had painted a large number, but as many as 140,000 people died in Hiroshima. As we continued painting, praying for the souls of the dead in the hope that it will never happen again, we realized that even if we painted all our lives, we could never paint them all. One atomic bomb in one instant caused the deaths of more people than we could ever portray. Longlasting radioactivity and radiation sickness are causing people to suffer and die even now. This was not a natural disaster. As we painted, through our paintings, these thoughts ran through our minds.

Iri and Toshi Maruki

As Rawlings noted, other Japanese artists did have a more “emotionally detached approach”, giving examples such as Satoshi Furui’s “photorealistic oil paintings of mushroom clouds” (Figure 3) which highlight “the paradox of the beauty in such destructive power.” This sense of the destructive power and beauty of the atom bombs crept into popular culture, where “themes of terror, monsters and mutation” run through many films of the 1950s and 1960s, such as those by the Toho Company, including Godzilla (1954) in which a nuclear test awakens the giant fire-breathing monster from its slumber in the sea and incites it to rampage through Tokyo, and Matango (1963), also known as Attack of the Mushroom People or Fungus of Terror, where a ship is wrecked on the island of Matango, an island used for nuclear testing, and as the film unfolds the survivors consume the mushrooms growing on the island, finding themselves slowly mutating into grotesque fungal creatures and turning against each other.

Time Bokan was a TV series that ran from 1975 to 1976 for sixty-one episodes. In the series the central character is the inventor of a time-travel machine, and he finds himself lost on a test run of the machine in the prehistoric past. Rawlings describes the end of each episode of Time Bokan as treating the atom bomb in a “more comical manner” where the “final eruption of a skull-faced mushroom cloud signalled the villain’s death.” Further towards the end of the 20th century, depictions of “futuristic scenes of a post-apocalyptic Tokyo” have appeared in anime such as Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira (1988) and Hideaki Anno’s Neon Genesis Evangelion television series (1995-96). Japanese film, TV and anime, including many remakes of these original films and series, continue these themes into the twenty-first century.

Japanese artist Takashi Murakami “responded to this conflation of Japanese wartime history with pop culture” in his own series of paintings, also titled Time Bokan (from 2001), which “depict the same skull-faced mushroom clouds as the original anime series, but with rings of smiling flowers in their eyes.” In 2005, at the New York Japan Society, Murakami delved further into the nation’s underlying nuclear anxiety when he curated the exhibition “Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture,” which covered everything from Godzilla figurines to Hello Kitty, and showcased the work of ten contemporary Japanese artists.

Writing in the Little Boy exhibition catalogue, Murakami suggests that the “post-war kitsch and childlike aesthetic of Japanese pop culture” is:

the product of generations struggling to internalize and rationalize the unprecedented trauma of the atomic bombings followed by the United States’ 1945-52 occupation of the country, which infantilized the Japanese people… It would not be an exaggeration to say that the American-made constitution prevented the nation from taking an agressive stance, and forced the Japanese people into a mindset of dependency under the protection of America’s military might.

Takashi Murakami

Murakami is critical of the situation where, after WWII, demilitarized Japan experienced a “collective sense of helplessness,” with the metaphor of Japan as the little boy is intended to critique the country’s supposedly unavoidable reliance on its big brother, America.

The name Little Boy, of course also references the code name used by the American military for the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945, and Murakami argues that “proliferation of ‘cuteness’ in Japanese contemporary art, which draws upon youth culture, especially otaku culture, evinces a common urge among the post-war generation in Japan to escape from their horrible memories and sense of powerlessness.” As Rawlings points out, “issues of infantilism aside, there is no doubt that Murakami’s idea is based on the truth that as the first country to sustain nuclear attacks, Japan suffered an unprecedented national trauma that has been sublimated into its post-war art and pop culture.”

Dong-Yeon Koh in his article “Murakami’s ‘little boy’ syndrome: victim or aggressor in contemporary Japanese and American arts?” goes further and describes Murakami’s rhetorical analysis of Japan’s self-image as “contradictory, given his extremely aggressive business tactics, which can find no counterpart in the Western art world – not even in the efforts of Murakami’s predecessor, Andy Warhol.”

Koh and Rawlings are keen to criticise Murakami’s theory as “flawed in that it frames the atomic bombings and Article 9 solely in terms of a binary relationship with the United States, portraying Japan as the exclusive victim of World War II,”. ignoring “Japan’s invasion and occupation of numerous Asian countries between 1894 and 1945 … in the name of liberating them from Western colonialism.”

Rawlings cites The Forbidden Box (1995) (Figure 5) by Hiroshima-based artist Yukinori Yanagi as an example of artwork that engages directly with Article 9. The Forbidden Box comprises iris and silkscreen prints on two nylon voile panels, each with a faded image of a mushroom cloud, overlaid with the original and later versions of Article 9, flowing out of a lead box, which has “Little Boy” engraved on its lid.

Before Japan’s surrender, Emperor Hirohito was seen as a direct descendent of the sun goddess Amaretsu, the most important Shinto deity; therefore, six days after the second bomb, at Nagasaki, when at noon on 15 August 1945, Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender on public radio, this was the first time the Japanese public had heard the Emperor speak, “and the realization that he was human came as an immense shock” to the people of Japan, and in 1946, on 1 January, Emperor Hirohito formally renounced his divine status in an “imperial rescript.”

The translucent layers of Yukinori Yanagi’s The Forbidden Box (Figure 5) can be seen as presenting viewers with “a visualization of the ambiguities in the pacifist ideology that redefined Japan’s position in the world.” The Forbidden Box alludes to the Greek myth of Pandora’s Box, as well the to the Japanese folk tale, Urashima Taro: in both stories the opening of the box spells chaos and trauma, and tellingly, with Taro the fishermen, when he opens the box “a white cloud emerges, causing him to age instantly and die” – the white cloud that ages Taro can be read as “the atomic cloud that rendered the emperor human.”

Although the atomic bombings are a pervasive theme in Japan’s visual arts, and have clearly conditioned much of post-war artistic production, they were only one of many issues confronting Japanese artists in the aftermath of World War II, and “should not be regarded as the single point of departure for all subsequent artistic and cultural expression in Japan.”

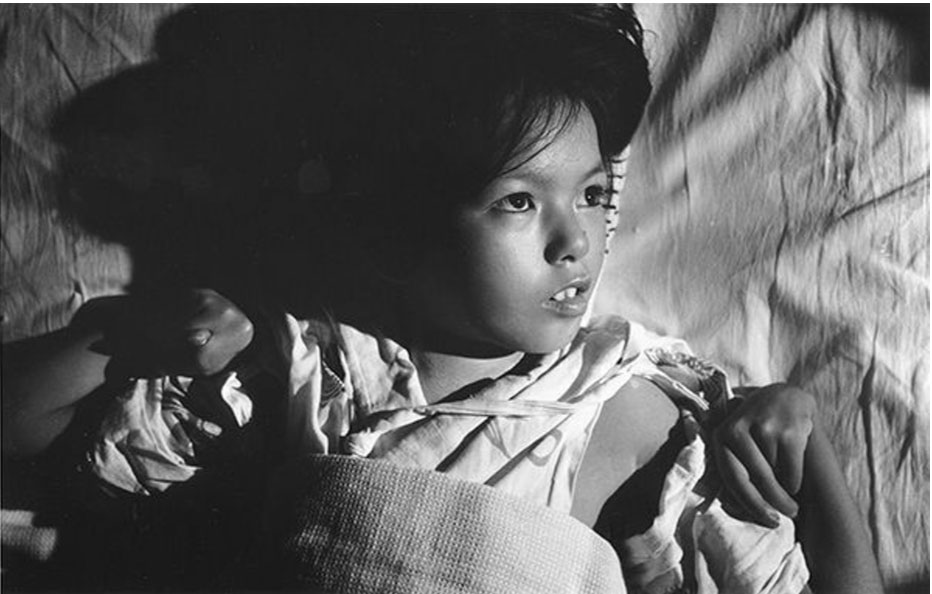

Japan has fallen victim to many disasters before and after the bombings, both natural and man-made, the latter from internal as well as external forces. Namiko Kunimoto in her book The Stakes of Exposure opens with documentation of the Minamata disaster which “unfolded across different media in a manner that heightened anxieties about bodily exposure in post-war Japan.” Kunimoto gives the poignant and pointed example of Kuwabara Shisei’s photo, Ikeru ningyō (A Living Doll), circa 1962 (Figure 6), which shows a young girl named Matsunaga Kumiko, who contracted mercury poisoning disease at the age of six, and died soon after.

The documentation by photojournalist and artists at the time gradually turned public opinion from that of fear of the victims as contagion, to outrage against the company responsible for the toxic pollution over many years. Kunimoto tells us that she opened her book speaking about the tragic events in Minamata because they “exemplify the intersection of gender, the body, nationhood, and representation” she sought to examine, noting that the disaster: “fed into other anxieties circulating in Japan in the post-war period—namely, that the physical body could not withstand exposure to the ravages of modern times, be they unknown contaminants in the air and water, the nuclear weapons wielded by the United States, or rapid changes to the urban environment. Fears about bodily contamination were also linked to the arrival of the Allied Occupation forces.”

In The Stakes of Exposure Kunimoto further devoted a chapter to each of four artists active in the post-war period: Katsura Yuki (1913–91), Nakamura Hiroshi (born 1932), Tanaka Atsuko (1932–2005), and Shiraga Kazuo (1924–2008) to show other artistic responses to the trauma experienced by the people of Japan before and after WWII. Today in 2022, at almost eighty years since the end of the Pacific War, Japan is still in the midst of a “turbulent process of national self-reflection and self-recognition.” Rawlings astutely noted that “although Article 21 of the constitution asserts the people’s right to freedom of expression and forbids censorship, in practice, artists and curators in Japan have to negotiate unwritten codes of decorum when exploring the atom bombings and the broader context of the country’s wartime past.”

It can be said that “art is in the eye of the beholder” and artwork dealing with traumatic events is even more sensitive to this subjective assessment. In many ways reception of such work is always going to be affected by time and space. A recent case was with the harshly critical reception of a piece by the Chinese activist and artist, Ai Weiwei, where he transported 14,000 life jackets used by refugees, for display in Berlin, his aim being said to be: “a tribute to the refugees that died at sea in an attempt to escape war and poverty in the Middle East and North Africa” – an aim met with angry retorts by some critics, such as “It would have been more useful to send and distribute them [the life jackets] in north Africa.” One wonders if the modern rhetorical phrase “too soon?” might be apt, even if the critics do have a rational and reasonable point. Such reception stands in stark contrast to the sympathetic viewing of the shoes left by Jewish victims of the Holocaust, displayed at Holocaust Memorial sites, which are today seen as “touching” and “moving;” both as a memorial to the victims and a memento mori to us now. Both views show that temporal and spatial concerns can, if not necessarily heal victims of trauma, allow for a possibly different reading of artworks made in response to traumatic events.

In some respects, as Eva Hoffman says in her introduction to After Such Knowledge, as such an “immense catastrophe recedes from us in time, our preoccupation with it seems only to increase” and yet there is the danger that “temporal, geographical, cultural” distance runs risks of “simplification implicit in such remoteness.” She questions how we can “apprehend” such trauma “from our distance”, what meanings do these events hold for us, “and how are we going to pass on those meanings to subsequent generations?”

Whatever the unwritten codes of decorum, or even stated laws at the time of traumatic events and the following periods, the way artists respond to trauma seems both relevant and ever-timely in the midst of the constant tide of extreme and transient events and consequences. “As we have seen, the stakes of these events were frequently – and perhaps most powerfully – communicated through art and visual culture.”

Further reading

Atomic Bomb survivors are referred to in Japanese as hibakusha, which translates literally as “bomb-affected-people” Bob Sink. ‘Who Are The Hibakusha? | Hibakusha Stories’. Accessed 8 October 2022. https://hibakushastories.org/who-are-the-hibakusha/.

Marianne Hirsch. ‘The Generation of Postmemory’. Poetics Today 29, no. 1 (1 March 2008). https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-2007-019

Eva Hoffman. After Such Knowledge: Memory, History, and the Legacy of the Holocaust. New York: Public Affairs, 2004.

Murakami, Takashi, ed. Littoru Boi: Little Boy, the Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture = Littoru Boi: Bakuhatsu Suru Nihon No Sabukaruchaa Aato. New York New Haven, CT: Japan Society, 2005.

Namiko Kunimoto. The Stakes of Exposure. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Ashley Rawlings. ‘Mutually Assured Decorum’. ArtAsiaPacific no. 65 (1 July 2009). https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=asu&AN=505255761&site=ehost-live

‘This Was Ai Weiwei’s Refugee Life Jacket Installation – Public Delivery’. Accessed 9 October 2022. https://publicdelivery.org/ai-weiwei-life-jackets/.